During World War II, US GIs had access to a variety of pin-up style men’s magazines, often referred to as “cheesecake”. The artwork might be drawings of girls or actual photos of models posing in a variety of burlesque, bespoke, and suggestive poses or scenes. These magazines were considered “pulp,” meaning cheap and disposable.

They rarely showed nudity in any mass-market commercial product, but a few like Gay Life (gay as in happy; produced from 1933?-1939? – link takes you to a magazine example with nudity) did. How this got around the Comstock Act, is anyone’s guess.

Some famous pin-up artists include Peter Driben, Alberto Vargas, George Petty, Vaughan Alden Bass, Al Buell, Earl Morgan, Billy De Vorrs (or De Vorss), and Gil Elvgren.

Some producers of Men’s Magazines include Robert Harrison, Brown and Bigelow, and Louis F Dow Co. (which was a calendar company)

Different magazines focused on different things, such as sadomasochism, “photostories” (which conceptually was created by Robert Harrison and consisted of scantilly clad girls doing routine things like moving furniture over 2-4 pages), interviews, violence/crime, gossip, humor, adventure/mystery/western/detective stories, breaking news type stories, celebrity scandal, and expose/investigative journalism, bawdy stories, letters from readers etc, but they all included a hefty dose of girls and content that appeal to the male gaze.

This article doesn’t purport to be a historical review of “Pin-Ups”; however, for a historical and academic discussion, see the Construction of the Pin-up Girl in US History.

The list below isn’t exhaustive, but only shows some representative examples. For a larger index of Men’s Magazines, see: Index of Men’s Magazines. For a general discussion of pulp magazines, Pulp International (link contains nudity) does a good job.

As in every industry, once someone figures out a winning formula, copycats come out. So, many of these magazines appear similar but are produced by different companies.

Suppose you want to think about the progression of “Girlie Mags that appeal to Men” on a timeline. In that case, it starts in the 1870s with dances like burlesque, belly dancing (especially with Fahreda Mazar aka Little Egypt), and striptease acts by the 1900s. As pulp magazines and film come around by the 1920s it’s “good looking girls” and sex-themed stories, to suggestive/implict in the late 1930s/1940s, to explicit but artistic in the 1950s (with the birth of Playboy and Marilyn Monroe posing nude), to explict nudie and sex films (think 1970s New York Times peep shows; and Deep Throat (film; link goes to wiki article), to mass market and commericalized pornography for porn’s sake in the 1980/1990s without any redeming artistic value. Each sort of decade has had US Supreme Court cases that begin to loosen standards, along with social and technological changes leading us to whatever it is we have now.

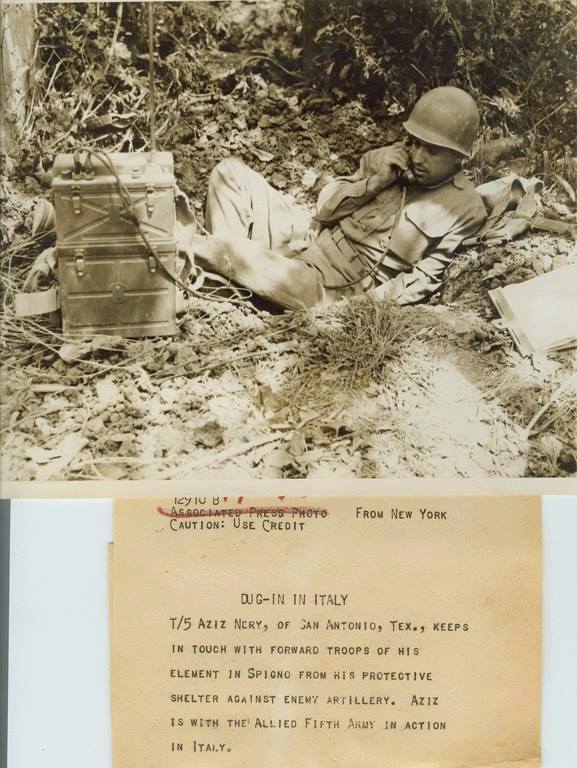

For a look at World War Two Civilian Magazines and Newspapers, check out the link.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Some of the magazines contain stereotypes of women, ethnic/racial stereotypes, implicit violence, non-consensual situations, sexual harassment, and other sexist attitudes that are objectively wrong by today’s standards. The author of this post rejects all of this and offers the information below for historical purposes to exemplify an aspect of World War II material culture.

World War 1 Era Magazines

Snappy Stories – Aug 1912 to 1933/1934. For a historical review, see Snappy Stories. For historical context, see: Viña Delmar, Flapper Fiction, and Snappy Stories Magazine.

Its name changed to Snappy Stories and Pictures in 1927.

The Parisienne – Jul-1915 – Aug-1915. Then from Sep 1915 to Feb 1921, as The Parisienne Monthly Magazine. Then from March 1921 to June 1921, as The New Parisienne Monthly Magazine. Then from July 1921 to April 1922, as The Follies. Finally, from May 1922 to July 1922, as Fascinating Fiction.

Originally named to help ride the wave of French propaganda coming ashore in the US amid WW1.

Gheesh, talk about a rebranding problem.

Breezy Stories or Breezy Stories and Young’s Magazine – The twin titles reflect periods where the publishers would oscillate between the two. Produced between Sept 1915 to Sept 1949.

Saucy Stories – Aug 1916 to May 1925. Then renamed Heart to Heart Stories from June 1925 to July 1925. Likely ceased publication in the mid to late 1920s.

1920s and 1930s Men’s Magazines

Spicy Stories – From Dec 1928 (Vol 1 No 1) to Oct 1928.

The magazine company Culture Publications was then pressured to “clean up” and introduced Spicy Detective, Spicy Adventure Stories, Spicy Western Stories, and Spicy Mystery Stories in the mid-1930s. The magazines augmented the sex appeal to include different kinds of stories to tamp down criticism.

The “Spicy” brand of magazines became very popular. For example, see this Sept 1936 edition.

Dec-1928 – 1930? The King Publishing Co., Dover, Delaware, produced it. In 1933, Merwil Publishing Co., Inc., 480 Lexington Ave., New York City, produced it. Publication lasted until the late 1930s and likely couldn’t translate into the “pin-up” era.

Other Pre-War magazines include: Paris Nights, Pep Stories, Ginger Stories, and Broadway Nights. For a review of popular “girlie pulp” magazines, see The Birth of the Girlie Pulp and 12 examples of Girlie Pulp.

Allure Magazine – Produced from July 1937 (Vol 1, No 1) to Sept 1937 by Yorkhouse Publications, 404 North Wesley Ave., Mt. Morris, Ill.

High Heel – Produced by Silk Stocking (Ultem Publications) between April 1937 (Vol 1, No 1) to 1939?

Silk Stocking – Probably starts in Sept/Oct/Nov 1936, (Vol 1 No 1). First called Silk Stocking Revue (Dec 1936), then changed to Silk Stocking Stories. Ended in 1939.

World War II Era Men’s Magazines

Beauty Parade: This was produced between October 1941 to February 1956 by Robert Harrison. It was one of the first magazines to capitalize on the “Pin-up” craze. He then went on to create Titter, Wink, Flirt, and Eyeful. See the Vol 7 No 3 1948 edition.

Titter: This was produced from Aug 1943 to April 1955 by Robert Harrison. Made famous due to a Band of Brothers, an HBO series, scene. The magazine is 8.5 wide and 11.5 high.

For an example of a post-war copy, see: Titter 1949 Vol 6 No 2.

Wink: This was produced between Summer 1944 to 1955 by Robert Harrison. For a full copy, see Wink Dec 1947.

Eyeful: This was produced between March 1943 to April 1955 by Robert Harrison. Later editions featured Bettie Page. It likely featured all of the popular burlesque, pinup, and stripper models in New York at the time. For a humorous analysis of the April 1949 magazine.

Jessica Rogers (the inspiration for Jessica Rabbit in the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit) was a model/dancer and posed for the magazine?

Giggles: Produced between 1943 to 1946.

Joker: Produced between Spring 1942 to? by Comedy Publications (which had the same Dunellen, NJ business address as Timely/Marvel publishing). Consists of pin-up girls and humorous cartoons. Interestingly, some of Marvel Comics’ illustrators would moonlight under different names for this magazine firm, as it was more adult.

Cutie – May-1944 to Oct-1946. The image is the last edition. A copy of Titter.

The Stocking Parade – Produced from July 1937 (Vol 1, No 1) to June 1943 by Arrow Publications.

Carnival – May 1939 to Jan 1940? It then combined with Show from June 1940 to November 1942 as Carnival Combined with Show (which is just objectively a bad name).

Laff – 1940 to probably the mid to late 1950s by Volitant Publishing. A humorous magazine. For a page-by-page breakdown, see Laff Magazine, Oct 1945. Marilyn Monroe (going by her name, Norma Jean, but misidentified as Jean Norman) was the cover model in the Aug 1946 edition.

This is a great write-up on Adrian Lopez, who created the magazine and went on to build an empire of bulk periodicals.

Gags – 1941 to 1942 by Triangle Publications. A copycat of Laff. The black dot that appears on the cover appears throughout the magazine and is a running joke.

You can download the full copies below. Size is 10 1/2-in. x 13 1/2-in and printed on cheap newspaper print.

Another example is called What’s Cookin! Which was made by the Comic Corporation of America, probably between 1942 to at least 1943. Same concept as Laff. You can view the Vol 1 No 7 Nov 1943 version here.

Post World War II Men’s Magazines

Flirt: This was produced between 1947 to 1955 by Robert Harrison. A pin-up style magazine with “photostories”, jokes, and men’s humor. You can review the Aug 1953 version here.

Confidential: This was produced between November/Dec 1952 to Aug 1958 by Robert Harrison. It was Robert Harrison’s best publication and focused on a lot of scandals, and is kind of a tabloid magazine. The decline of his WW2 “pin-up” magazines and his refusal to do full frontal nudity spreads led him to create this one. Though, he was eventually sued and forced to sell it. It continued publication until 1978.

Whisper: This was produced between April 1946 to probably 1958 by Robert Harrison. It consists of recycled stories from Confidential.

Glance – 1948-1952 by Cape Magazine.

Showgirls – Produced only from 1947 to 1948 by Your Guide Publications. For Vol 1 No 3 from July 1947, see this link.

Cover Girl Models – 1949-1955 by Models Publishing Co

Vue – 1950s to ? The image shows Marilyn Monroe in the August 1952, January 1955, and August 1955 editions.

The Korean War

G-Eyefuls: A Manual of Arms and Legs – By Bill Boltin 1951. A pin-up style book marketed towards soldiers in the Korean War. Burlesque queen Lili St. Cyr appears twice.