2009 #SUMMEROFPAT SONG

The Official 2009 #SummerofPat song: Chllin by Wale

2008 #SUMMEROFPAT SONG

The Official 2008 #SummerofPat Song:

In the Ayer by Flo Rida

Lowes Musings

Was at a big box store over the weekend and found a few things I thought were amusing:

LAMP Stack – Iykyk

Oh, the irony –

This is a stupid selling point –

BUY THESE ROCKS THEY WON’T DECAY!

Though here is the crazy thing, rocks decay (erode) after millions of years.

Phablet

For Valentine’s Day I got the wife a new phone. We had discussed the possibility of her getting an Ipad but the price was a bit steep. I was willing to take the plunge on an Ipad for her (and of course secretly use it when she wasn’t looking).

In the end, the Samsung Note 4 turned out to be a good option that combines the two (phone and tablet) into one device called a Phablet. She also looked at cases for the phablet and it turns out they make cases that resemble books for note. Though you must be a Moby Dick fan as that is what their bookcases come in.

From a historical perspective, I do find it odd that in the recent history of mobile phones, the race was to go from the Gorden Gecko Motorola DynaTAC of the 1980s and make it smaller. The film Zoolander even had a joke about the ever-decreasing size of phones:

Now it appears technology is racing to make the phones bigger.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Resume

Resume as seen here

“My Most Illustrious Lord,

Having now sufficiently seen and considered the achievements of all those who count themselves masters and artificers of instruments of war, and having noted that the invention and performance of the said instruments is in no way different from that in common usage, I shall endeavour, while intending no discredit to anyone else, to make myself understood to Your Excellency for the purpose of unfolding to you my secrets, and thereafter offering them at your complete disposal, and when the time is right bringing into effective operation all those things which are in part briefly listed below:

1. I have plans for very light, strong and easily portable bridges with which to pursue and, on some occasions, flee the enemy, and others, sturdy and indestructible either by fire or in battle, easy and convenient to lift and place in position. Also means of burning and destroying those of the enemy.

2. I know how, in the course of the siege of a terrain, to remove water from the moats and how to make an infinite number of bridges, mantlets and scaling ladders and other instruments necessary to such an enterprise.

3. Also, if one cannot, when besieging a terrain, proceed by bombardment either because of the height of the glacis or the strength of its situation and location, I have methods for destroying every fortress or other stranglehold unless it has been founded upon a rock or so forth.

4. I have also types of cannon, most convenient and easily portable, with which to hurl small stones almost like a hail-storm; and the smoke from the cannon will instil a great fear in the enemy on account of the grave damage and confusion.

5. Also, I have means of arriving at a designated spot through mines and secret winding passages constructed completely without noise, even if it should be necessary to pass underneath moats or any river.

6. Also, I will make covered vehicles, safe and unassailable, which will penetrate the enemy and their artillery, and there is no host of armed men so great that they would not break through it. And behind these the infantry will be able to follow, quite uninjured and unimpeded.

7. Also, should the need arise, I will make cannon, mortar and light ordnance of very beautiful and functional design that are quite out of the ordinary.

8. Where the use of cannon is impracticable, I will assemble catapults, mangonels, trebuckets and other instruments of wonderful efficiency not in general use. In short, as the variety of circumstances dictate, I will make an infinite number of items for attack and defence.

9. And should a sea battle be occasioned, I have examples of many instruments which are highly suitable either in attack or defence, and craft which will resist the fire of all the heaviest cannon and powder and smoke.

10. In time of peace I believe I can give as complete satisfaction as any other in the field of architecture, and the construction of both public and private buildings, and in conducting water from one place to another.

Also I can execute sculpture in marble, bronze and clay. Likewise in painting, I can do everything possible as well as any other, whosoever he may be.

Moreover, work could be undertaken on the bronze horse which will be to the immortal glory and eternal honour of the auspicious memory of His Lordship your father, and of the illustrious house of Sforza.

And if any of the above-mentioned things seem impossible or impracticable to anyone, I am most readily disposed to demonstrate them in your park or in whatsoever place shall please Your Excellency, to whom I commend myself with all possible humility.”

Ideologue Amendments

Vox has a pretty good article on the schisms and breakpoints in American democracy: American Democracy is Doomed. The article came out in 2015 but is still absolutely relevant.

The article in Vox suggests that the current system is flawed. I’d argue the system is not flawed but the people in it are. Specifically, I target gerrymandering as an origin point. What’s gerrymandering you say? Note, that the video does play.

Studies have shown that when like-minded groups of people get together (say crammed into a voting district that is majority one-party) they tend to deviate towards the extreme. After all, the only way you can “prove” yourself is to be more extreme than the other guy. Thus, we end up with elected ideologues in government, particularly in Congress.

As a political scientist, I found the reading a timely topic. I had read The Broken Branch by Mann and Orstein (a pair of poly-sci guys) and found their argument favorable. Congress is broken and needs to be fixed by fixing how ideologues get elected.

As a follow-up, This is How American Government Will Die explains that we will end up with some sort of benevolent/elected dictator in about 50 years if we cannot change. I can see the allure of a Cincinnatus-like figure taking over in support of the Common Good.

I would tend to agree, though, that a dictatorship, even an elected one, is one dictator too many. Especially, after the recent court decision in Trump vs US, which granted the president criminal immunity for his Article II actions and presumed immunity for “official acts” (which the court declined to outline). This is the first time in US History that a person is above the criminal law. This makes the US a quasi-dictatorship.

I think what we need to consider is one of two possibilities:

A. An entire rewrite of the Constitution. Most countries (and states!) re-write their Constitutions every couple of years. France has had five and my state of Virginia has had seven since 1776. America is the exception rather than the rule.

B. Add new amendments. We added amendments to counter the power of Big Business (think your Progressive Era amendments: 16, 17, 18, 19). Perhaps we need new amendments to counter the power of ideologues. I’d start with:

28th. An anti-Gerrymandering Amendment to ban it. In doing so, I’d consider having the House of Representatives ignore state boundaries when creating districts. An idea James Wilson originally had at the convention.

29th. Federal Elections must be financed publicly using public money. Our current mess of electoral finance results in Congresspersons beholden to the wrong kind of special interests. Congresspersons essentially are “tin-pot dictators” who can get elected by throwing around enough money and then passing laws based on who donated the most rather than the common good.

30th. Make Federal Election voting mandatory. 50% turnout makes governing difficult. By law, Congress could make Voting Day a paid national holiday. Or provide a tax incentive like a credit for voting. Could make it just a box you check that you voted or not. Obviously, the IRS probably isn’t going to follow-up on everyone but you always run the risk of getting audited and the IRS can look into whether or not you lied on the box.

31st: Junk the Electoral College. It’s anti-majorian.

32nd: Age limits for Presidents and Court Justices.

What other amendments would you add?

WW2 Signal Corps and Communication Paperwork

Below is a collection of Signal Corps-related paperwork for use in WW2 Reenacting.

Radio

Templetone Model BP2-A5 Log Card – The Templetone Model BP-2A5 seemed to be some kind of morale radio for the troops. The log card would be placed under the front-cover so it would show when the cover was opened. Not sure why a morale radio would need a station log card?

Print in medium-weight beige cardstock. Print on both sides of the media and cut at crop marks to produce one Station Log card.

For a good history of the radio see: Templetone Model BP2-A5 “Morale Radio”.

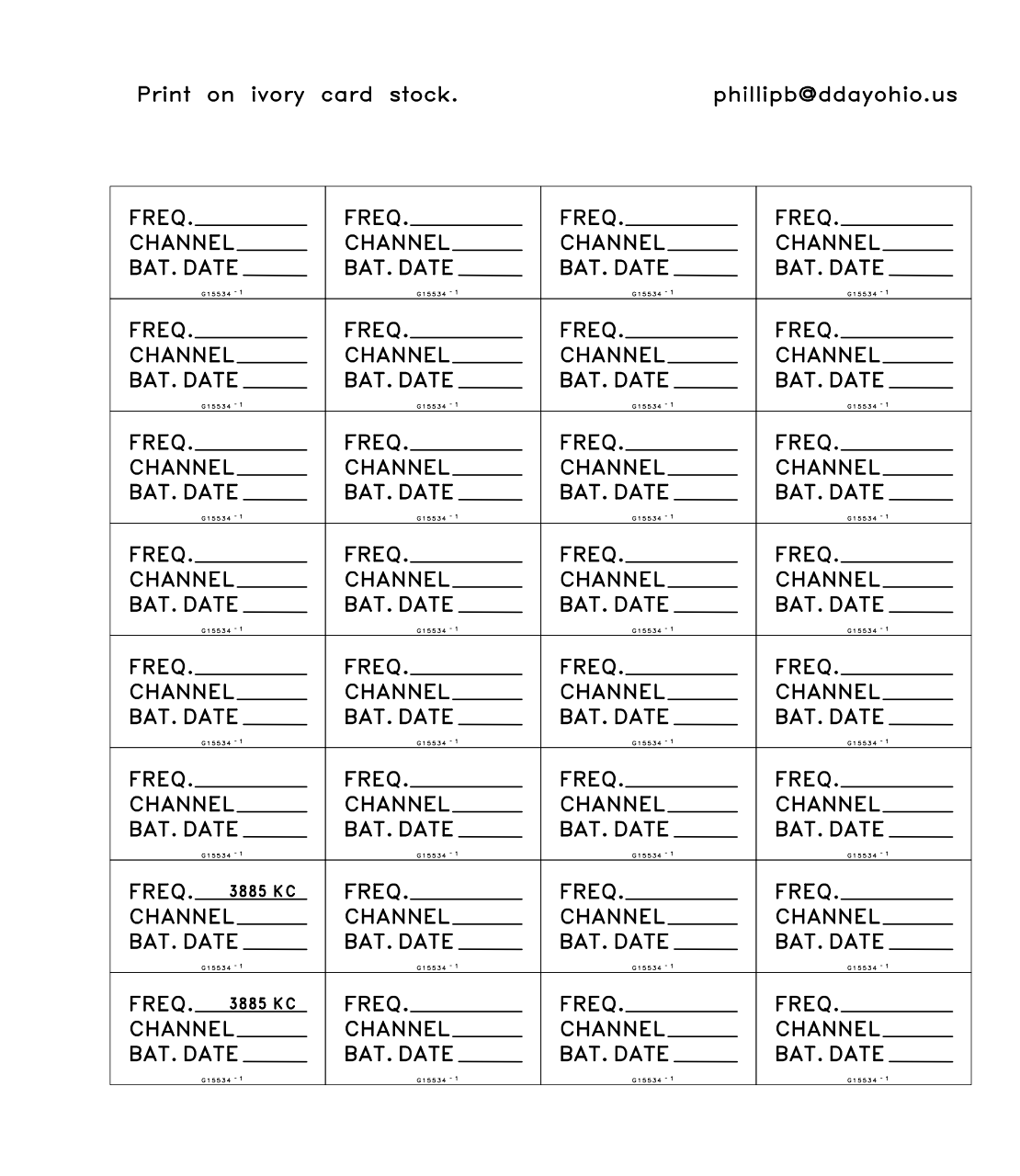

BC-611 Frequency Card – This is the card that would go into the small window of the BC-611/SCR-546 radio

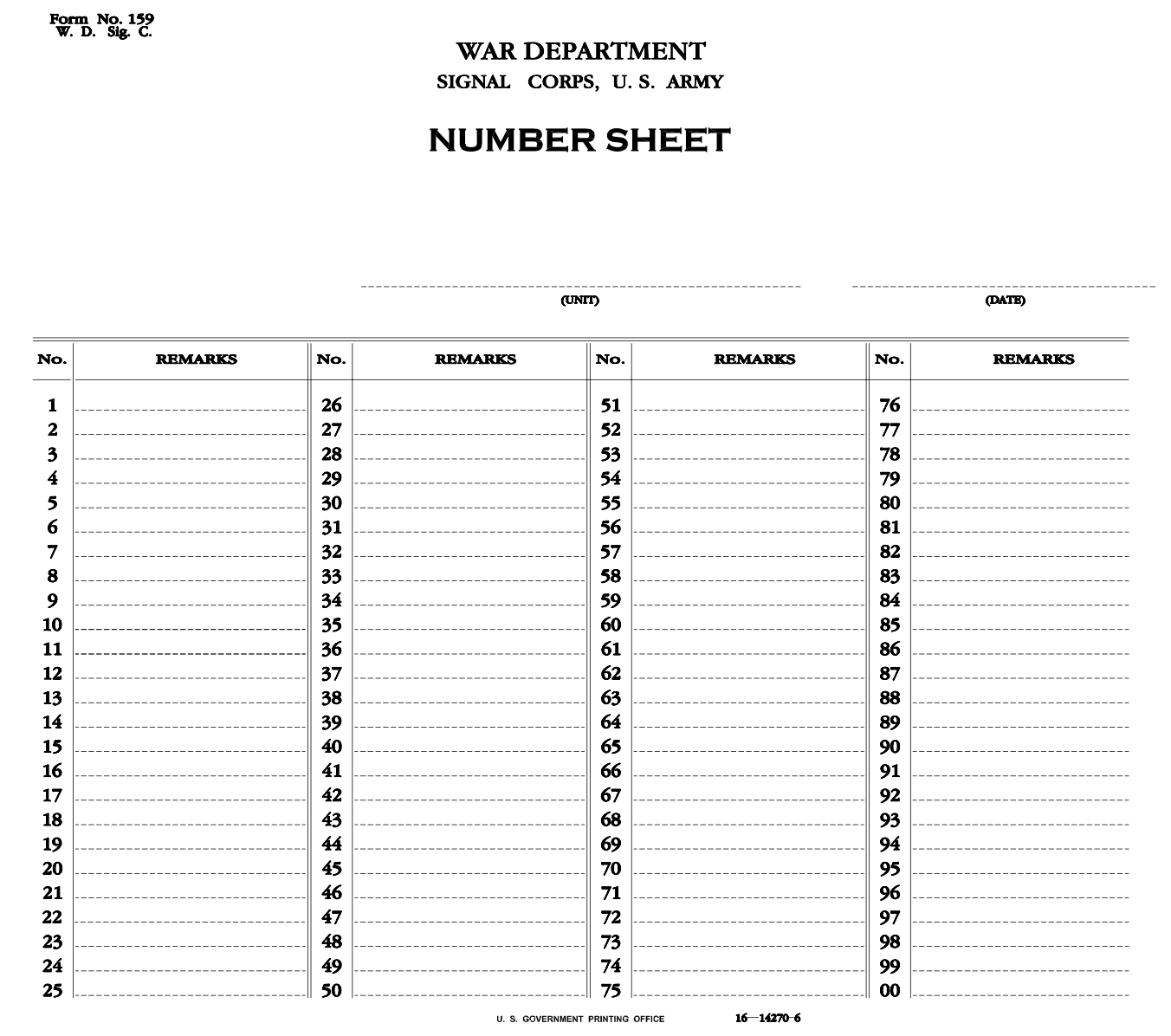

Form 159 – Number Sheet | Print pages on natural or ivory paper and stack+trim to the same size. Run a few beads of rubber cement along the top edge to have a tear-away stack.

I’m unsure what this was exactly used for.

Telephone

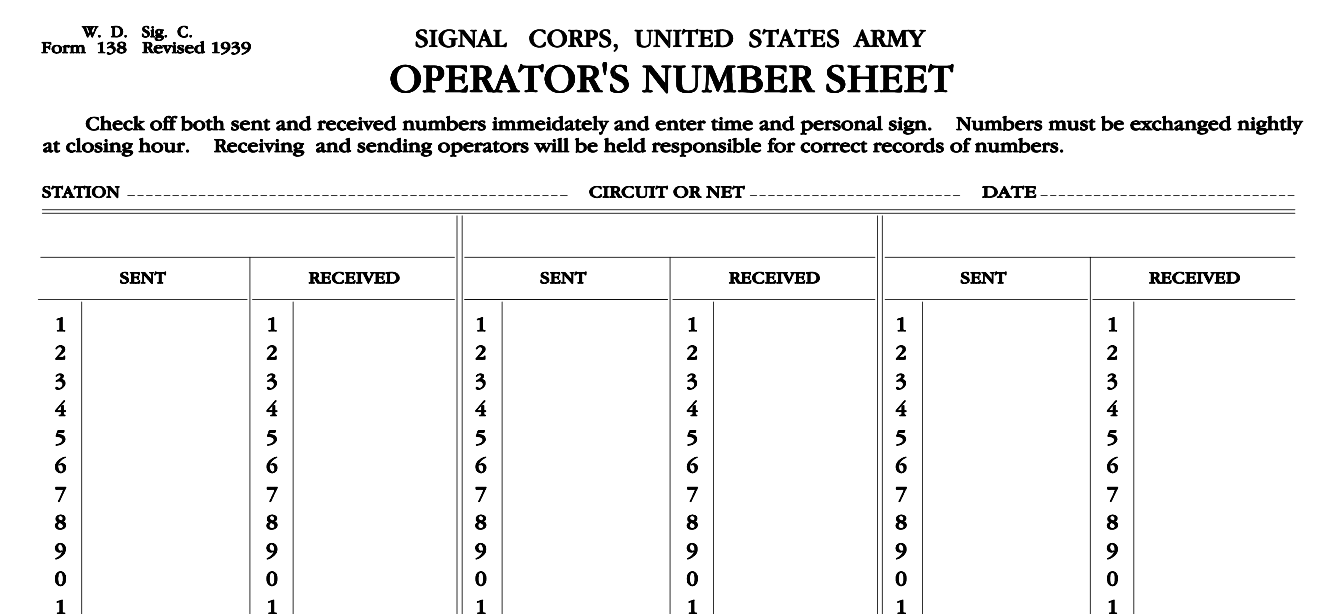

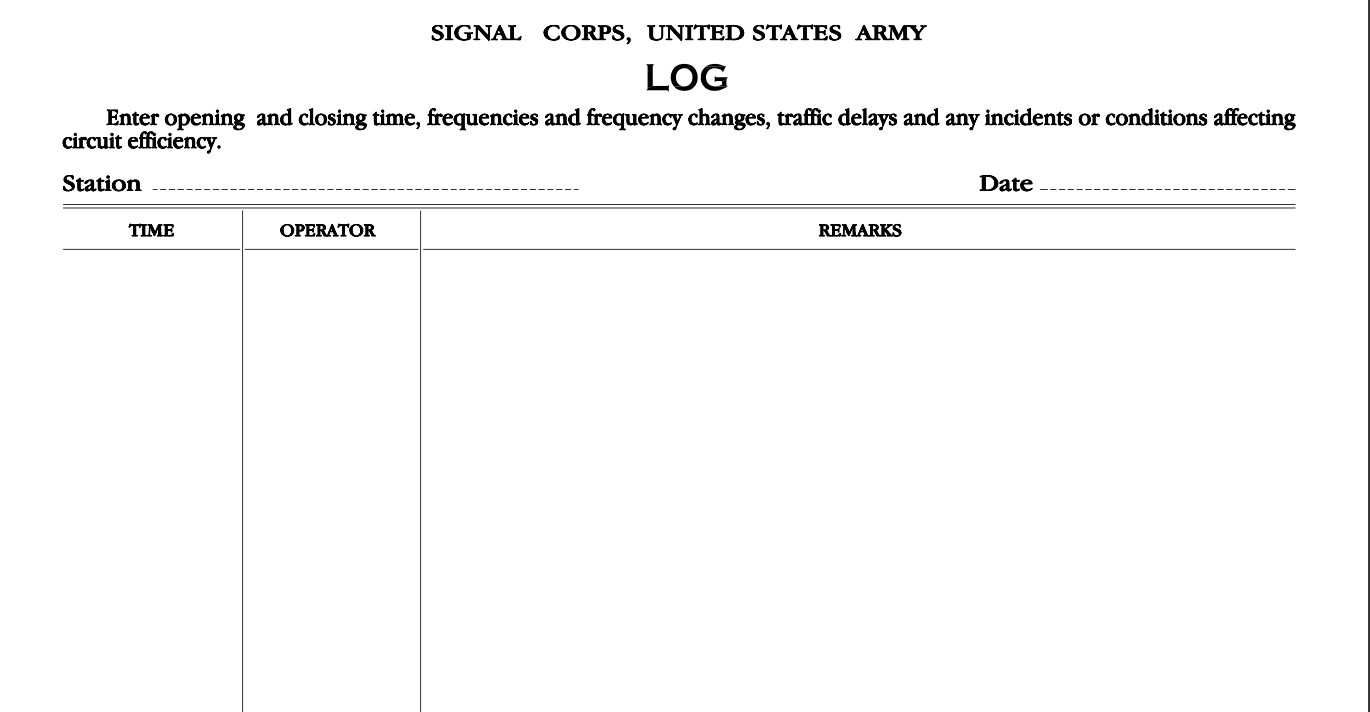

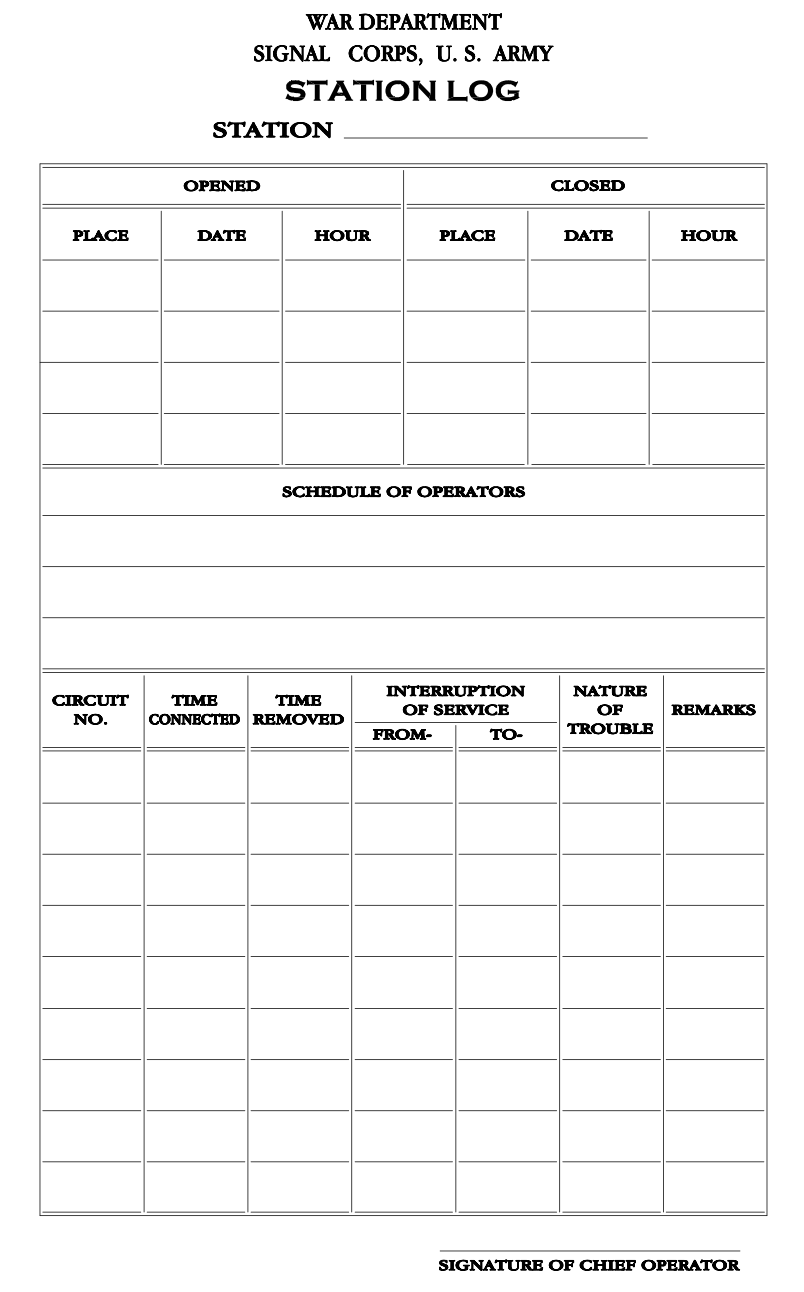

Signal Corps Station Log – Signal Corps paperwork to record traffic at what appears to be a telephone station. Form number unknown.

Print pages on natural or ivory paper and stack+trim to the same size. Run a few beads of rubber cement along the top edge to have a tear-away stack.

Other

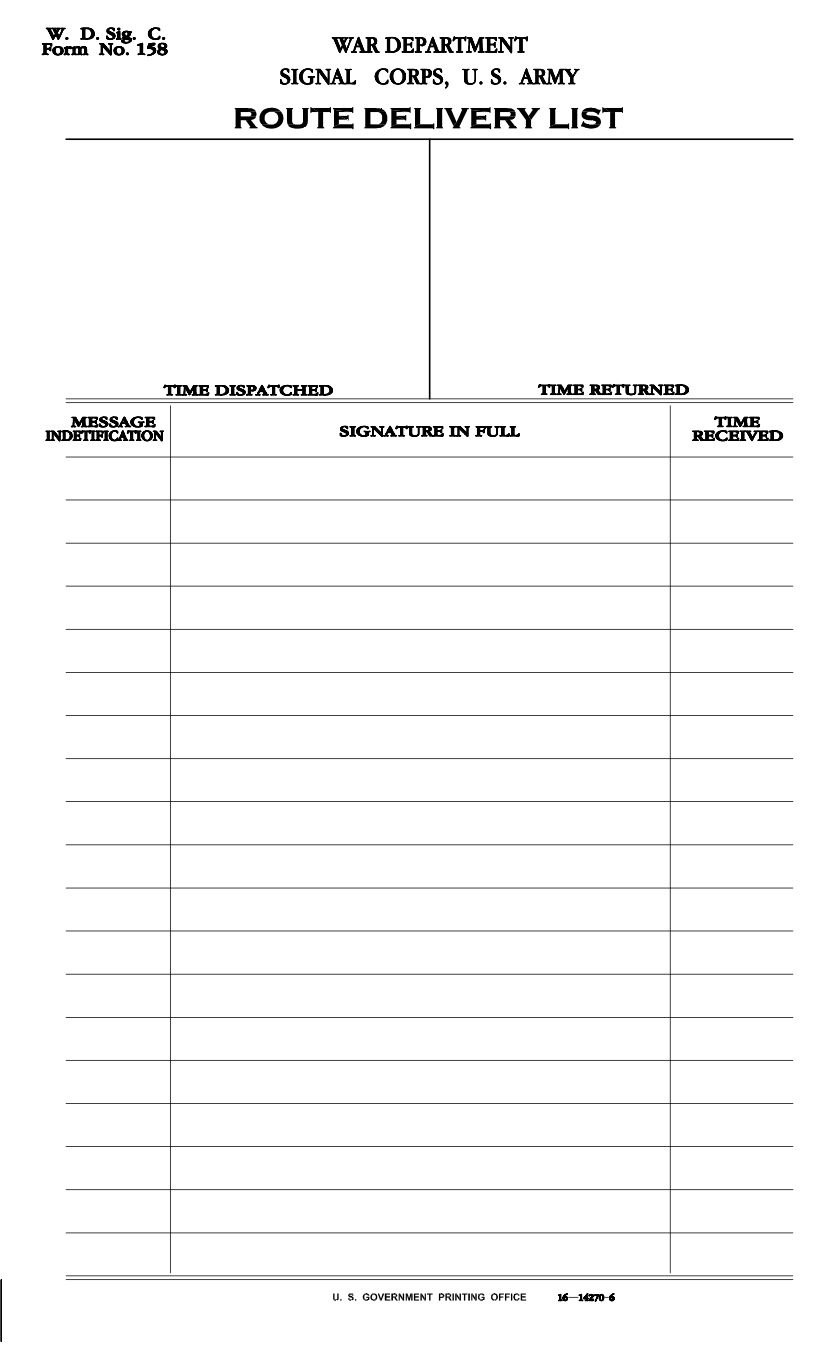

Form 158 – Route Delivery List – Signal Corps form for delivering messages. Print 25 pages on natural or ivory paper and stack+trim to the same size. Run a few beads of rubber cement along the top edge. You’ll have a tear-away pad of 50 sheets.

A “route delivery” seems to connect more points.

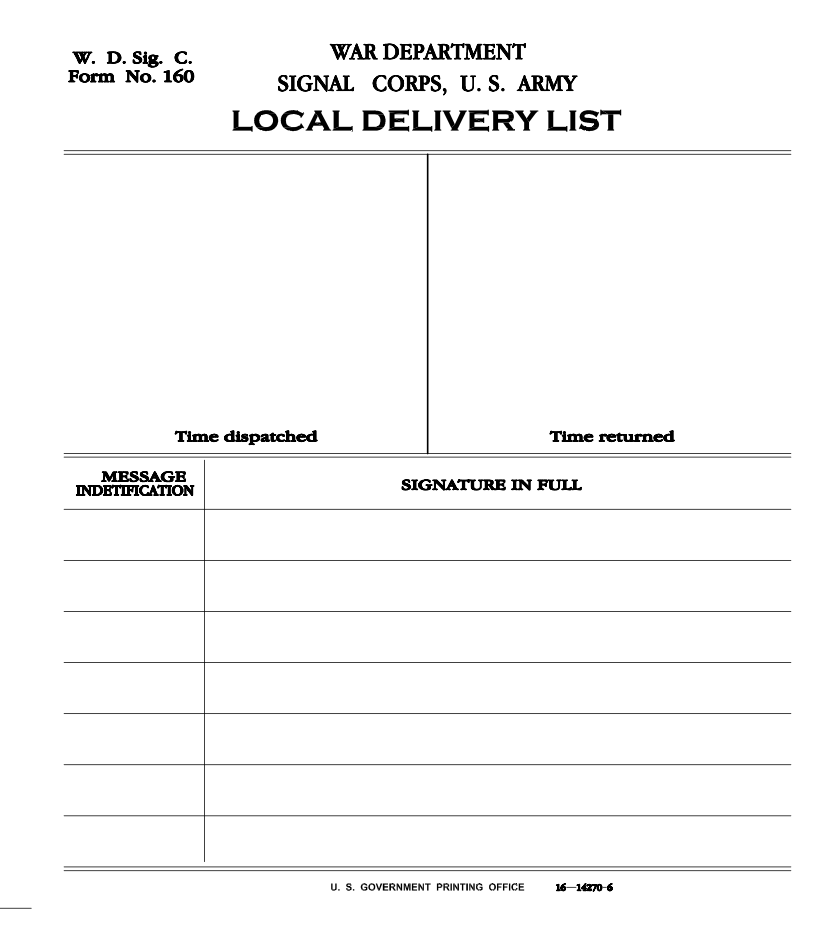

Form 160 Local Delivery List – Signal Corps form for delivering messages. Print 25 pages on natural or ivory paper and stack+trim to the same size. Run a few beads of rubber cement along the top edge. You’ll have a tear-away pad of 50 sheets.

A “local delivery” seems to connect fewer points.

Message Book M210a Front and Inside – A printable pdf file for the M201a message book. This book would be used in a message center. It would be unlikely to appear in a map case. You can download the front+back here and the insides here.

Print on regular paper and then trimmed to size. The book has overall dimensions of approximately 6-1/8″W x 4-1/4″H x 1/2″ thick. Inside the book are 25 each triplicate message forms for regular use, three each duplicate forms for carrier pigeon use, and 25 sheets of tracing paper. The back cover has an extension that can be placed under the topmost form, so that it can be filled out without marking the carbon-copies of the following forms. The book also includes instructions for its use and a list of authorized abbreviations.

For best results, print on 8-1/2″ x 11″ US letter-sized paper with no scaling. Finished forms should be 4.75in wide by 4.25in tall.

When cutting it out, save 1/4 inch of space on the left-hand side. That way the staples don’t go through the message part.

I’m not sure if anyone is reproducing these but if they are I’ll add a link. Note that this only includes a single blank message form and not the carbon copies or map overlay.

Now there’s also an M 210-B message book which looks like it came out in late 1944. This is according to the Signal Corps Technical Information Letter Nov 1944 No 36. The major differences are some measurement tools on the front-cover, the removal of the pigeon forms and map overlays. This was all done to help speed up the message processing as it was found soldiers experienced difficulty removing the copies in the M210a book.

There’s also an M-105-A message book. I’m not sure what the difference is. If I found I’ll write about it.

Signal Corps Technical Information Letters

Signal Corps Technical Information Letter No 18 – May 1943. Outlines new training methods, procedures and equipment. One interesting story is how local police captured an illegal pinball den and donated the machines to Ft. Monmouth to be used as needed.

Signal Corps Technical Information Letter No 36 – Nov 1944. Outlines new training methods, procedures, and equipment. Discusses the fungi and moistureproofing techniques (which is some kind of lacquer spray), as well as the Silica Gel, used to pack equipment and an anti-radio jamming exercise among other interesting and nuanced signal corps minutia.

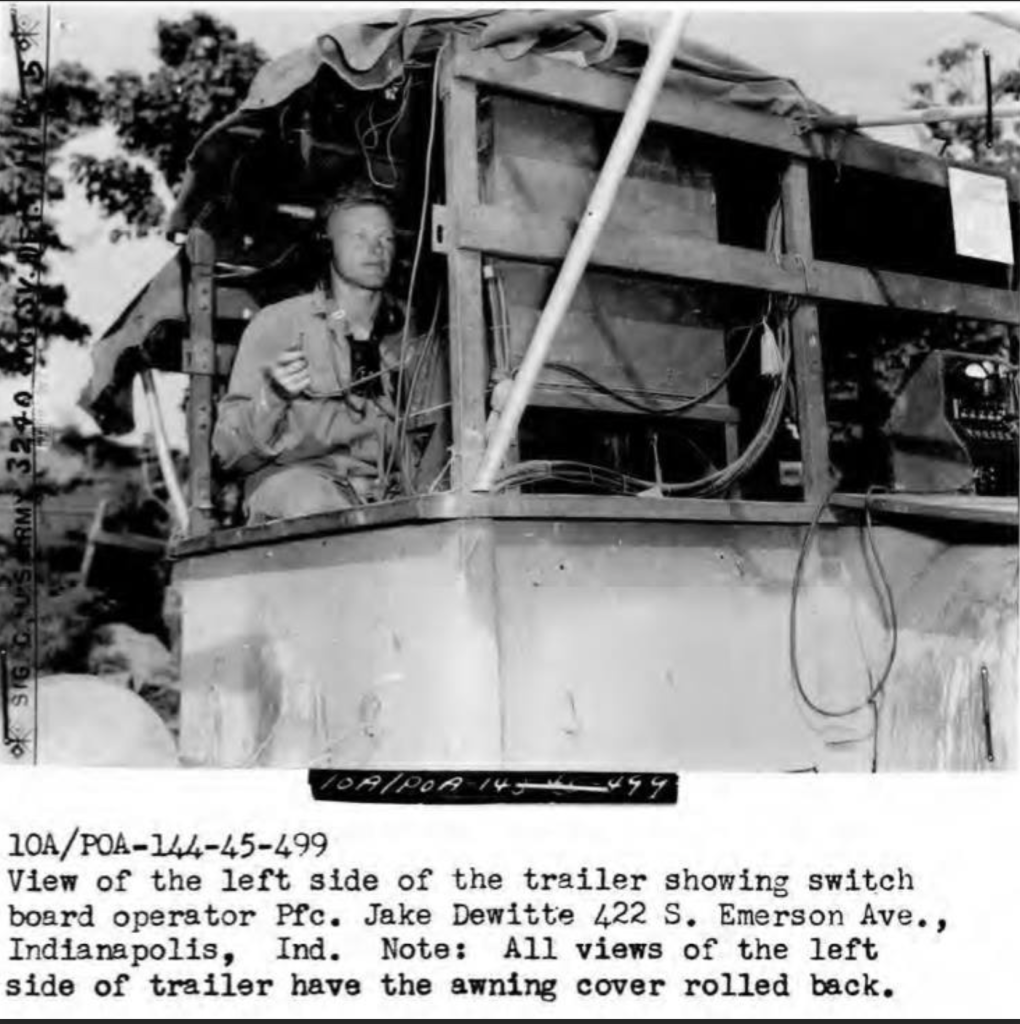

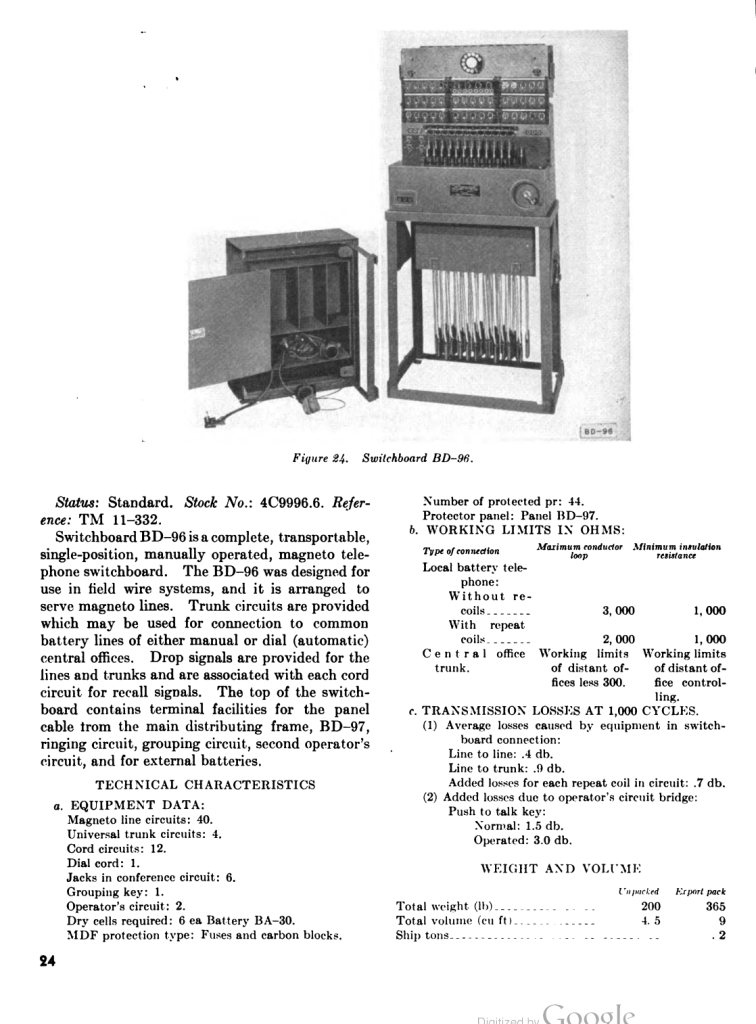

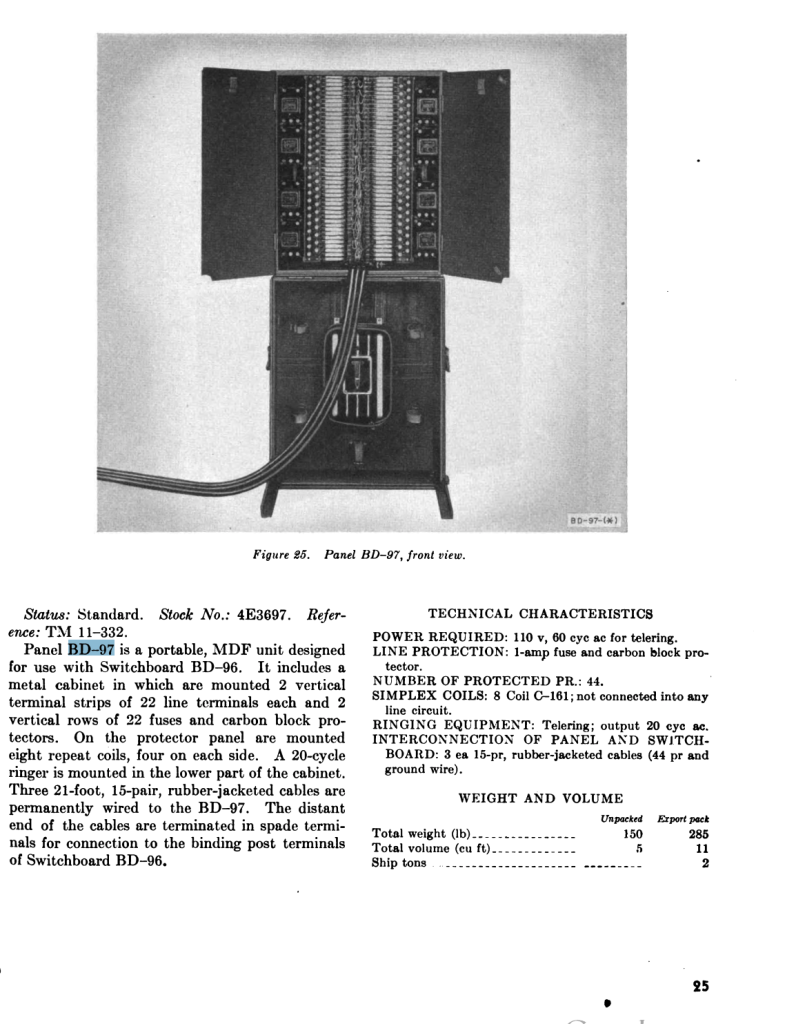

27th Signal Company Switchboard Trailers – During the Phase 1 Nansei Shoto Operation on Okinawa, the 27th Signal Company of the 27th Infantry Division created a special trailer to house a BD-96 switchboard and it’s BD-97 panel, test sets, EE8 field phones and other incidentals required to operate a BD-97 switchboard in a combat operation. The BD-96 is used to run up to 40 lines into it.

The trailer was used to be as mobile as possible during the operation. Being mounted in a trailer makes it so.

This type of configuration may have been used at the Battalion or more probably at the regimental level.

BD-96 and BD-97 images come from: TM 11-487B Directory of Signal Corps Equipments: Wire Communication Equipment.

Basic Wire Communication: Lineman’s Handbook: Wire Training Section Central Signals Replacement Training Center, Camp Crowder Missouri – This is a printable booklet and gives a very quick review of wire splicing, terminology, and organization

TM-184a Terminal Board Fabrication – This is a pdf that shows the schematics of how to fabricate the TM-184a terminal board. It is used as a terminating or test point in tactical field wire systems.

TM-184 T1 and T2 replace this. You can view the instructional manual for them here.

TM-184a and T1 and T2 hold 7 pairs wires. TM-84 holds 5 pairs of wires.

US Navy Uniform Regulations 1941 to 1946

1941 Uniform Regulations, with Wartime Amendments

The U.S. Navy’s uniform regulations of 1917 were revised and published in 1941, however, the 1941 edition was obsolete by the time it went to print. Habitual indecisiveness and reneging with regard to uniforms are apparent in the sheer number of changes and amendments made to these regulations during the war.

In some cases, uniform insignia was introduced one month and abolished the next. Additionally, unauthorized insignia was often designed, produced privately, and worn on uniforms without authorization only to be approved for wear retroactively at a later date by the Navy. Other insignia worn by men of special units were never authorized for wear by the Navy. At the onset of World War II in 1941, the Navy provided a large number of uniform options for both officers and enlisted.

Many of these optional uniforms were considered superfluous to the war effort and abolished. Many pre-war uniform accouterments were made of metal wire, bullion, or other materials that could be put to better use in the manufacture of ships, vehicles, aircraft, and munitions. Two examples of wartime conservation of uniform ornamentation were bullion rating badges and officer’s swords, both of which were no longer required after 1942. Other uniforms were abolished simply to conserve the textile materials used in their production. In addition to abolishing older nonessential uniform items, new uniforms and accessories were introduced during the war.

All of these constant changes to the regulations made them impossible to enforce. Consequently, the wartime regulations are also very difficult to organize and list as a historical reference as well.

The following is the complete 1941 Uniform Regulations as they were published in May of that year. Amendments made to these regulations between 1941 and 1947 are provided as an appendix. Due to the complexity, redundancy, and impossibly confusing nature of the Uniform Regulations before the 1948 revision, no collection of the wartime Navy regulations has ever been compiled into one publication. To the best of the author’s knowledge, the following is the first attempt to organize, catalog, and record all of the regulation amendments put into effect between 1941 and 1947.

Unlike the U.S. Army’s uniform regulations of World War II which are a matter of record and easily obtainable, this provides a complete set of wartime Navy uniform regulations for the first time in over half a century.

Download the US Navy Regulations Here from my Google Drive

Overview

Page 1:

The cover of the U.S. Navy Uniform Regulations as they were published in May 1941.

Pages 2-195:

The complete and unedited 1941 uniform regulations.

Pages 196-211:

The following regulation amendments are transcribed here from handwritten memos and slips of paper pasted into a revised set of regulations. The date of the letter or authorization documentation is provided in parentheses “( )” when available. Note that the following regulation amendments refer to a specific article of the 1941 regulations. For example, an amendment beginning with the numbers “2-86” refers to articles 2-86 of the 1941 regulations concerning caps. The abbreviations; BP CL or BuPers = Bureau of Naval Personnel Circular Letter and BN CL = Bureau of Navigation Circular Letter.

Pages 212-221:

These documents are the actual typewritten regulation amendments that were distributed in the form of “Circular Letters”. As regulations were changed, news of these changes was delivered to ships and stations in a memo format called Circular Letters. These were to be pasted into existing copies of the 1941 Uniform Regulation book as they were received. Obviously, the huge number of Circular Letters that were distributed during World War II couldn’t all be pasted into one volume so many were lost or misplaced. It is important to note that many Circular Letters addressed several regulation amendments over a period of years. For example, a letter dated January 1946 may in fact be in reference to amendment changes authorized in 1944 and 1945. This was typically the case and it was common for amendments to be consolidated and distributed a year or two after their inception. With this, amendments with post-World War II dates should not be dismissed as post-war revisions. The following regulation changes refer to the wearing of insignia and ribbons.

Pages 222-238:

The following regulation changes refer to the wearing of insignia and ribbons.

Pages 239-287:

The following are general regulation changes concerning the Naval uniform of officers and enlisted men from 1941-1947.

Spectacles and Glasses in WW2

Spectacles had been provided in World War One, but it was not anticipated that this service would again be required. It was believed that the Red Cross would provide any needed spectacles. The only provision for the Army to provide spectacles was found in Army Reg. 40-1705, which authorized procurement only when they were necessary to correct visual defects resulting from violence suffered in the performance of duty. In all other cases the Army doctors would write prescriptions and the soldiers would have to pay out of pocket.

The problem became clear after the first draft when soldiers couldn’t afford out-of-pocket glasses or had broken their personal ones and couldn’t afford new ones. The military glass frame was to be 10% nickel silver with a reinforced bridge. It was found that this frame corroded in hot weather causing discoloration of the skin. An 18% nickel silver frame with the pad arm, pad arm assembly, endpieces, and cable winding of pure nickel solved this problem.

This was essentially the Ful-Vue style of glasses with the P3 frame that GIs wore.

Each man was entitled to two glasses. However, delivery problems abound. It took 5 months to get all the materials needed to make glasses and due to this instead of a 3-day turnaround period, it wasn’t unusual to have a 3-4 months turnaround period for the glasses. Some men never received the glasses, other men got them months and sometimes years later, as the glasses would be forwarded to the post where the men would be, only to find out that the said soldier had moved on.

Part of the problem lay with instead lay with 20% instead of 10% of the men needing glasses and not having enough materials to meet demand. The biggest problem, however, was that the eye examiners kept the receipts from the eye exam 7-10 days after, then forwarded all the accumulated receipts to the optical company.

The optical company couldn’t fill all the orders at once and so a backlogged ensued. Making the desired 3-day turnaround period impossible to fulfill. The frames were about $1.00 and the lenses about 75 cents. The average total cost of a pair of eyeglasses was about $2.50.

See: United States Army Medical Department – Medical Supply in WW2 1968 pp.75-80.

There are several other well written guides that go into glasses in more detail. Such as P3 Glasses – The U.S. Military Spectacles, GI Glasses: Are Modern Reproductions Worth It?, and Four Eyes: Eyeglasses and the WWII GI (a link to my Google Drive for a pdf).