A collaborative effort between historical reenactors of how to use the SCR-300 Radio for World War Two Reenactments.

The SCR-300 Radio is a backpack (or manpacked) FM radio designed during WW2 as an inter-company or regiment radio. I purchased several in the late 1990s during the heyday of Cold War surplus sales.

Several years ago I worked with a buddy of mine to make available a resource that World War Two SCR-300 enthusiasts could use to analyze and learn about the radio. The article is posted on his website:

Radio and Telephone Procedure

For a full breakdown of how to communicate over radios and telephones please refer to: FM 24-9 BASIC FIELD MANUAL COMBINED UNITED STATES-BRITISH RADIOTELEPHONE (R/T) PROCEDURE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1942.

BC-1000 Control Panel Fasteners

BC-1000 Control Panel Fasteners – This is a pdf that covers how to add new washers, seals, nuts, and screws to the front panel. Looks to be about 8 different screw assemblies.

NOTES from TM 11-242 on the SCR-300 Wired Loops and Battery Case Catches

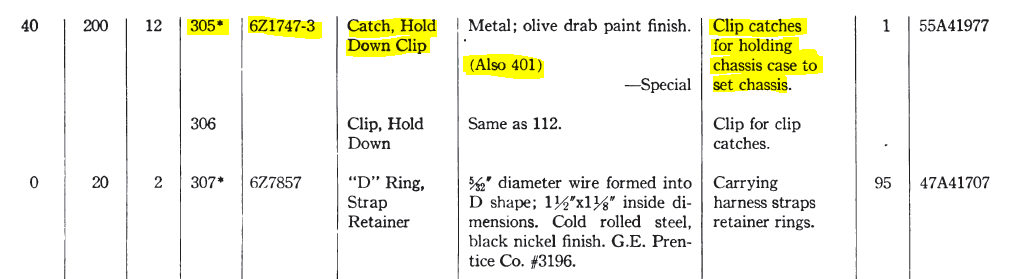

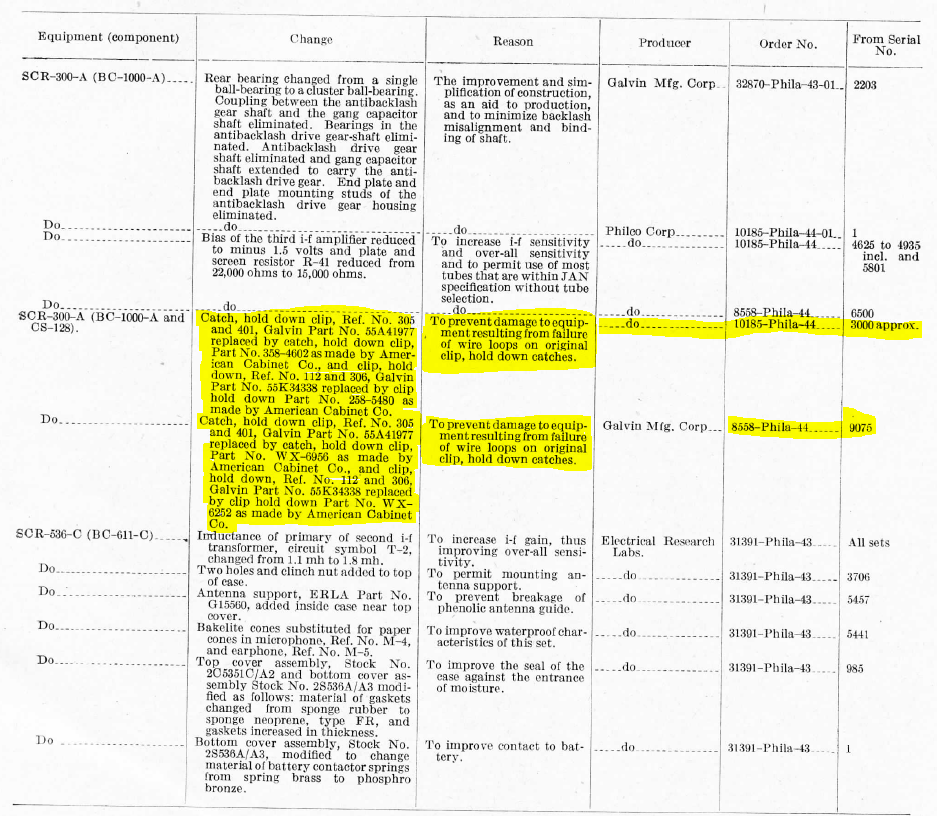

The SCR-300 originally came with wired clips. This is according to TM 11-242, 1943. See below

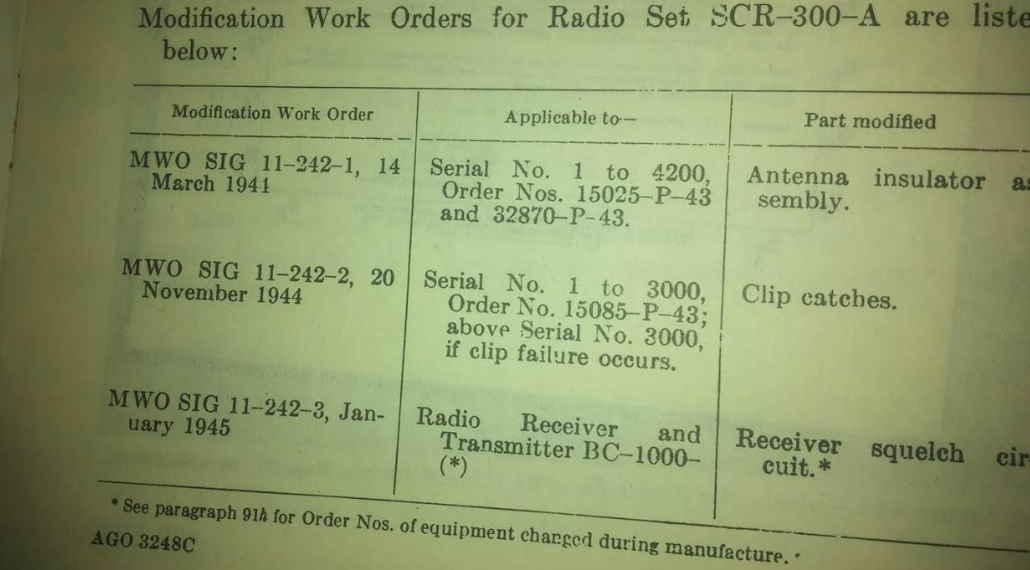

A work order was made in Nov of 1944 for spring catches

This was then replaced with a New Latch Directive in Jan 1945. The wired loops would fail to hold down the clip so a spring catch was added.

SCR-300 Radio Set: The Development, Operational Employment, and Details of the Famous “Walkie-Talkie”

Mike Roof, SGM, USA (ret.) wrote a 200-page guide on the development of the radio set which includes great discussions of some of the early war development and post-war variants. As well as new images of the SCR-300 in WW2. Worth checking out to learn a bit more about the unit. He originally posted it in the G503 forum but it looks like space might be an issue for him so I re-posted it here.

Combat Lessons

Below are some nuggets of information regarding Radio Security and Lessons Learned while using Radios in World War Two. It was taken from Hardscrabble Farm and reposted here.

Combat Lessons 3: The snippets below come from this guide. You can find the full guide via a pdf which contains a variety of information at my Combat Lessons and Army Talks Post.

Common Violations of Radio Security Brigadier General Richard B. Moran, Chief Signal Officer, Fifth Army, Italy: “Use of proper names, Christian names, nicknames, etc. to refer to an officer or enlisted man defeats the object of daily changing code signs and helps to identify groups. The authorized code or codex must be used.

“Use of unauthorized code names or codewords may cause confusion. Units may not allot them without permission.

“Long transmissions give the enemy plenty of time to tune in and increases his chances of gleaning information. Keep ‘off the air’ if possible. Keep transmissions short.

“An encoded map reference must not be accompanied by a description of the place referred to.

“Administrative reports must not be sent in the clear. The enemy can often obtain valuable information from them.

“Codex is more secure than the reference-point code and its use should be encouraged.”

Disclosed by Your Code Official Report, Signal Operations, Sicily: “The continued use by an organization of a code of their own making will easily identify that unit wherever and whenever it moves. Members of a unit captured by the enemy disclose the unit designation. As long as the unit uses its special-type code its identification is certain.”

Combat Radio Log

This is a pdf of a Radio Log by the 60th Infantry Regiment of the 9th Infantry Division between Sept 14th to Sept 21st. This was part of the attack through the Huertegen Forest. This kind of radio log probably wouldn’t have been transcribed by an SCR-300 radioman but it gives an idea of radio communication in an actual combat situation.

This looks like regimental-level radio traffic as the operator interacts with different units such as Nudge, Notorious, Red, Blue, Nomad etc. Many have a numbered suffix at the end like “Nutmeg 3” or “Blue 3” suggesting they are part of the same radio traffic net and are either a specific person or unit (like a battalion or company) within the said net.

In looking at it I think when the mention Nutmeg Red or Nutmeg White or Nutmeg Blue (etc) it’s likely the regimental or battalion and Nutmeg Blue 2 (for example) is some additional subdivision like battalion or company?

The 84th Infantry Division Signal Operation Instructions for Radio and Telephone standard operating procedures goes into a bit more detail about how call signs work on both radio and telephone. It approximates the radio log of the 60th. Namely, the Signal Officer assigns the code names, frequencies, and effective dates, and provides for the radio and telephone equipment. If a subdivision is needed they refer to it as a color and if an additional subdivision is needed, they use a letter.

So if I’m using an SCR-536 at the regimental level and I want to contact the D company of the 1st battalion of the 334th Infantry Regiment I could tune to the frequency and say something like ” This is Chow contacting Chisel Blue D”

Note that telephone would be utilized over radio (but uses a similar communication style) unless the officer thinks radio warrants it or they need it for an emergency.

For a listing of Military Code Names in Europe see: Military Code Names for the full listing or this Excel sheet for a breakdown by division. I’m not sure if it’s all of them or if these were dynamic and changed but it’s a piece of paperwork someone would’ve had. These codenames were likely at an Army or Corps level echelon as opposed to a division or regiment or battalion or company.

They also describe the various positions of the units as they move forward clearing out bunkers and pill-boxes. At one point they make mention of losing the slidex which is a handheld encryption device.

For reference the following units are

Nutmeg = 60th Infantry Regiment

Nostrum = 9th Medical Battalion

Notorious = 9th Infantry Division

Noxema = 15th Engineer Battalion

Nudge = 39th Infantry Regiment

Nuptial = 60th Field Artillery Battalion

Nostril = 47th Infanry Regiment

Omaha = 3rd Armored Division

Jacket = 4th Cav Group

Jingle = 438th AAA AW Bn M. Meaning it’s the 438th Anti-Aircraft Artillery, Auto-Weapon Battalion, Mobile. I’m not sure what the “auto-weapon” the unit had is supposed to be.

Jungle = ?

Batteries

Hardscrabble Farm has a write-up on Batteries: BA-23 and BA-30. These aren’t used in the SCR300 but I posted them here as they are commonly used with various Signal Corps telephone and radio equipment. BA-30 is the equivalent of a D battery.

Crystals

Radios in WW2 and in some post-war models like the PRC6 used crystals. CR is the Army nomenclature for the crystal. Several different kinds existed such as CR-18U and CR-23U. The numbers at the end likely refer to the type of crystal structure.

The crystal structure would give an indication of how well the drive, power, ohm level, and oscillation of the crystal would perform. For a complete breakdown of the science behind it, you can refer to: HANDBOOK OF PIEZOELECTRIC CRYSTALS FOR RADIO EQUIPMENT DESIGNERS by John P. Buchanan, Philco Corporation, October 1956. It’s a 700-page tome!

The crystals were then cut to oscillate at certain frequencies. They were then stored in signal corp metal cases typically starting with CS or CY.

The video below discusses How Crystals Go to War and shows the manufacturing process.

For an excellent short history of the crystal industry in the US up to the end of the Korean War see: A History of the Quartz Crystal Industry in the USA published by the UFFC the organizing body to set standards for crystals today.